You have an important message to deliver. Perhaps it’s warns of an imminent danger. Or it provides key support to injured plaintiff, a great cause or a high quality product. But no matter what you’re trying to communicate, the value of the message is just one part of the equation. When you’re trying to persuade others, the spokesperson’s acceptability to the audience can be even more important than the quality of the message. The greatest expert will not convince people if they do not recognize his expertise, or if they question his honesty or impartiality. Scientists have devoted years of research to the question of what makes any presentation more likely to persuade its audience. Here’s a little of what they learned.

You have an important message to deliver. Perhaps it’s warns of an imminent danger. Or it provides key support to injured plaintiff, a great cause or a high quality product. But no matter what you’re trying to communicate, the value of the message is just one part of the equation. When you’re trying to persuade others, the spokesperson’s acceptability to the audience can be even more important than the quality of the message. The greatest expert will not convince people if they do not recognize his expertise, or if they question his honesty or impartiality. Scientists have devoted years of research to the question of what makes any presentation more likely to persuade its audience. Here’s a little of what they learned.

The Image of Expertise

Eminent social psychologist Dr. Elliot Aronson wrote some twenty years ago, “Careful experiments have shown that a judge of the juvenile court is more likely than most other people to sway opinion about juvenile delinquency…and that a medical journal can sway opinions about whether or not antihistamines should be dispensed without a prescription.” So, science confirms what common sense tells us: People are most likely to follow Virgil’s advice, “Believe an expert.” So, they look to an authority. Or at least someone they perceive to be one.

Eminent social psychologist Dr. Elliot Aronson wrote some twenty years ago, “Careful experiments have shown that a judge of the juvenile court is more likely than most other people to sway opinion about juvenile delinquency…and that a medical journal can sway opinions about whether or not antihistamines should be dispensed without a prescription.” So, science confirms what common sense tells us: People are most likely to follow Virgil’s advice, “Believe an expert.” So, they look to an authority. Or at least someone they perceive to be one.

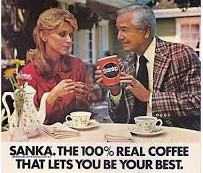

Influence expert Dr. Robert Cialdini cites the case of Robert Young, the highly successful spokesman for Sanka Coffee in the 1970s and 80s. Young was no expert on coffee or caffeine. He was, though, a highly recognizable actor who played Dr. Marcus Welby in the then popular television series. Young was not a doctor, but fans thought of him as one. Sanka sales soared when their campaign featuring him began. People felt as if their doctor had told them to cut down on caffeine and gave them an acceptable way to do it.

Influence expert Dr. Robert Cialdini cites the case of Robert Young, the highly successful spokesman for Sanka Coffee in the 1970s and 80s. Young was no expert on coffee or caffeine. He was, though, a highly recognizable actor who played Dr. Marcus Welby in the then popular television series. Young was not a doctor, but fans thought of him as one. Sanka sales soared when their campaign featuring him began. People felt as if their doctor had told them to cut down on caffeine and gave them an acceptable way to do it.

What if you don’t have a real expert or someone who looks like one?

It’s easy to put together a credible campaign if you have a recognized authority on the subject at hand or at least someone who plays one on TV. But often, marketers must work with much less. How can you increase your message’s believability? Psychological research highlights two ways.

Dr. Aronson and his coauthor write, “Several years ago, we and our colleague Judson Mills did a simple laboratory experiment demonstrating that a beautiful woman – simply because she was beautiful – could have a major impact of the opinions of an audience on a topic wholly irrelevant to her beauty.”

Dr. Cialdini provides an example from marketing research. “In one study, men who saw a new-car ad that included a seductive female model rated the car as faster, more appealing, more expensive-looking, and better-designed than did men who viewed the same ad without the model. Yet when asked later, the men refused to believe that the presence of the young woman had influenced their judgments.”

Dr. Cialdini provides an example from marketing research. “In one study, men who saw a new-car ad that included a seductive female model rated the car as faster, more appealing, more expensive-looking, and better-designed than did men who viewed the same ad without the model. Yet when asked later, the men refused to believe that the presence of the young woman had influenced their judgments.”

Research shows that good looking people are seen as more talented, kind, honest and

intelligent. Thus, if no expert spokesperson is available, an attractive one provides a good substitute. Some products or causes, though, don’t lend themselves to campaigns using great looking models as spokespeople. What then?

The magic bullet

Fox News chairman Roger Ailes once served as an advisor to the campaigns of Presidents Reagan and Bush. Note his comments on the characteristics of a great presenter:

If you could master one element of personal communications that is more powerful than anything we’ve discussed, it is the quality of being likeable. I call it the magic bullet, because if your audience likes you, they’ll forgive just about everything else you do wrong. If they don’t like you, you can hit every rule right on target and it doesn’t matter.

Research shows that Ailes is right. A spokesperson doesn’t have to be Albert Einstein,  Jennifer Lopez or Brad Pitt to be effective. But they must be likeable. ‘All things being equal,’ states Dr. Cialdini, ‘people prefer to do business with someone they like. And when all things aren’t equal, they still want to work with someone they like.’

Jennifer Lopez or Brad Pitt to be effective. But they must be likeable. ‘All things being equal,’ states Dr. Cialdini, ‘people prefer to do business with someone they like. And when all things aren’t equal, they still want to work with someone they like.’

Credibility can be manufactured

A study done by Dr. Aronson and his colleagues Elaine Walster and Darcy Abrahams reveal a way to manufacture credibility. This experiment presented participants with a concocted newspaper article relating an interview with a fictitious mobster, Joe “the Shoulder” Napolitano. In the article perused by one group, Joe “the Shoulder” argues for stricter courts and more severe sentences for serious crimes. The other group read about an interview where Napolitano advocated for more lenient courts and penalties that were far less harsh.

A study done by Dr. Aronson and his colleagues Elaine Walster and Darcy Abrahams reveal a way to manufacture credibility. This experiment presented participants with a concocted newspaper article relating an interview with a fictitious mobster, Joe “the Shoulder” Napolitano. In the article perused by one group, Joe “the Shoulder” argues for stricter courts and more severe sentences for serious crimes. The other group read about an interview where Napolitano advocated for more lenient courts and penalties that were far less harsh.

Not surprising was the fact that those who read this fictitious criminal’s appeal for less prison time found it totally unconvincing. What was remarkable was that when he argued for stricter courts and tougher sentences, Joe “the Shoulder” was extremely effective. By advocating a position that is clearly against his own self-interest, Napolitano convinced readers that there must really be something to what he was saying. When a real-life criminal, Ted Bundy, admitted in a pre-execution interview that a boyhood addiction to crime novels and a teenage fascination with violent pornography led to his becoming “the only man in America with a PhD in serial murder,” it was easy to believe him.

Therefore, to increase your presentation’s chances with the public, hire an expert, an attractive model or highly likeable spokesperson. If none is available, methods like arguing against your own self-interest can increase your believability. Other ways exist as well. If you’d like to learn more about bolstering your chances of having audiences pay attention to your messages and act on them, please email me at larryrondeau@gmail.com.